Exploiting macOS PKGs Part 1: Abusing open in Postinstall Scripts

Diving into a potentially dangerous use of the open command within macOS PKG pre/postinstall scripts, and how it might be abused. My victim for this research was the Zwift app.

Something Interesting Found

While starting my research into vulnerable macOS PKG’s, I stumbled upon a simple, yet interesting method of auto-starting a macOS application that is installed with a PKG. The specific PKG was for Zwift, an application designed to link to a bike trainer for indoor training coupled with a nice GUI for riding virtually.

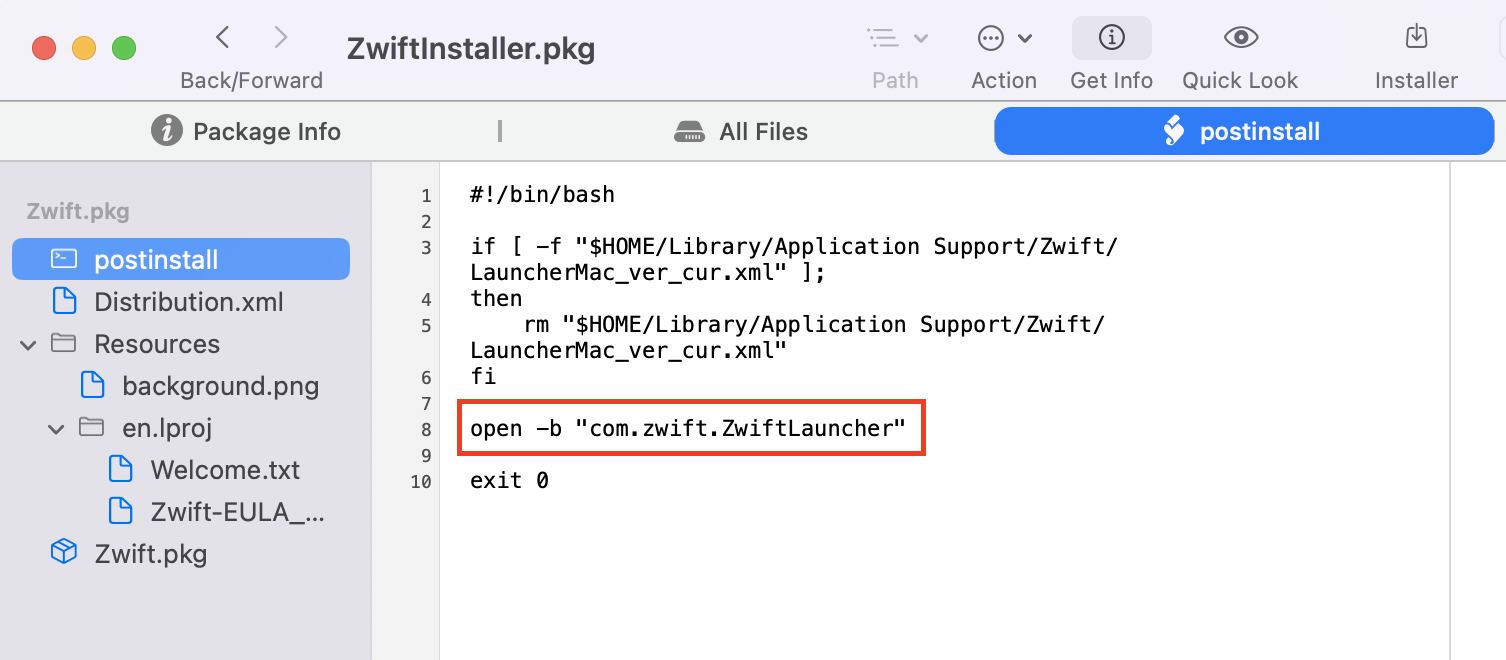

Within the PKG’s postinstall script is the below command, which is the last comand executed by the Zwift PKG installer, and which will start the Zwift application.

open -b "com.zwift.ZwiftLauncher"

At face value, this command makes perfect sense. Once the application is installed, the app’s bundle ID is automatically registered with Launch Services database, so running open using the bundle ID is reliable, right? Not quite.

The Launch Services Database

The macOS Launch Services is responsible for a lot of things, including:

- Associating file types with applications (e.g., .pdf → Preview)

- Registering URL schemes (e.g., http:// → Safari)

- Managing default applications for file types

- Handling “Open With” menu options

- Tracking installed applications

But this is not a deep dive into Launch Services, as I’m only interested in the last responsibility listed above.

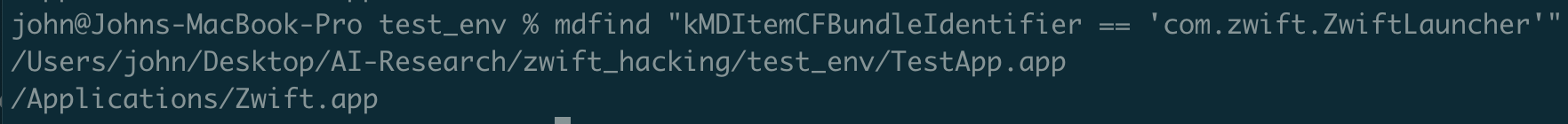

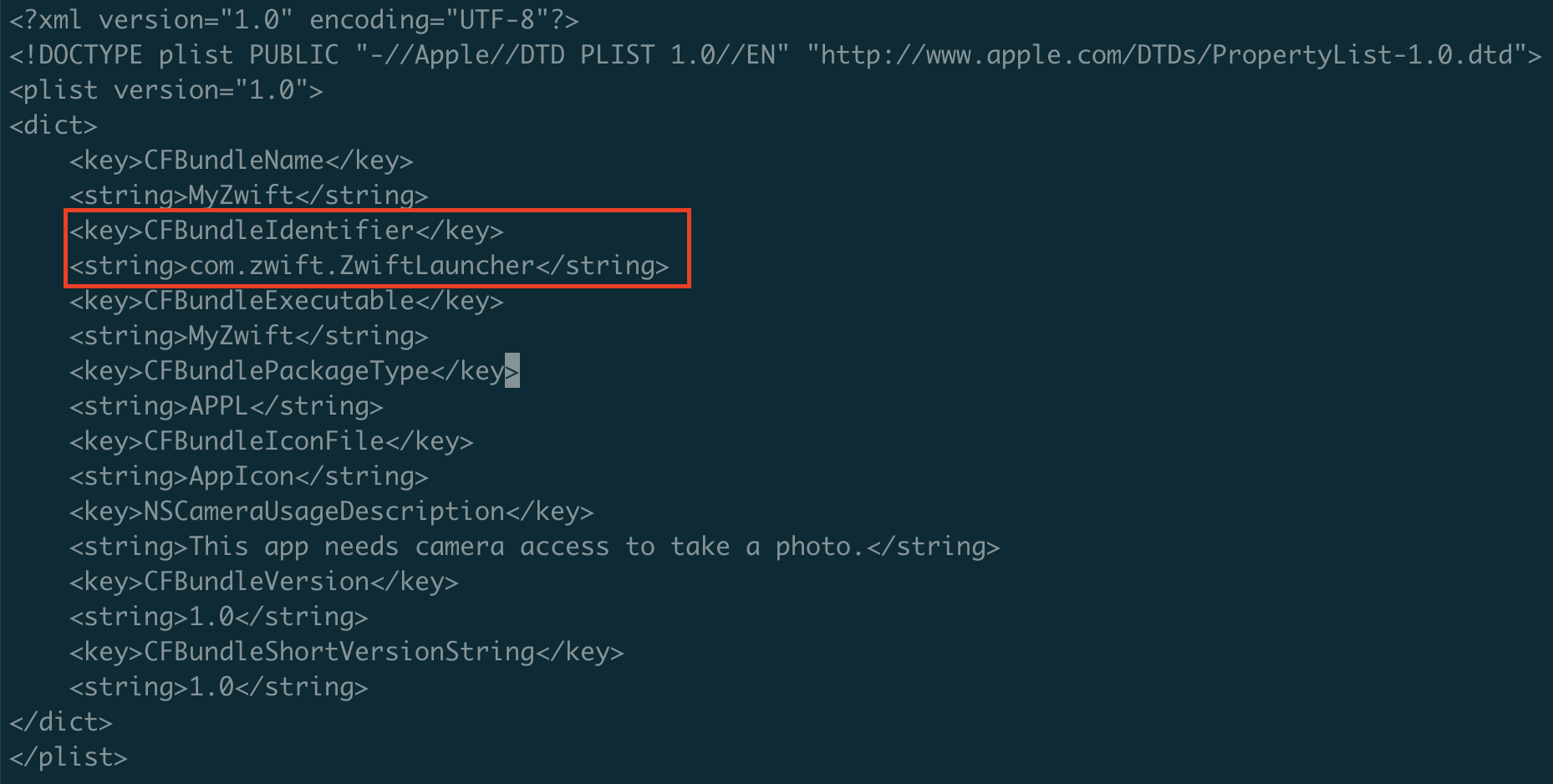

When a .app directory structure lands on the macOS filesystem, within a few seconds the app will be scanned and registered within Launch Services. This is done regardless of if the app is notarized or codesigned. When scanning and registering the newly introduced app, the Info.plist file is where most of the information it needs for registering the app lives. This information includes the application name, the path to the application’s executable binary, and the application’s bundle ID (e.g. com.zwift.ZwiftLauncher).

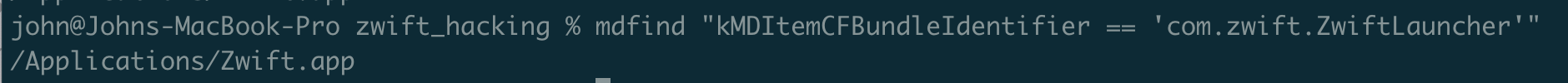

An interesting behavior of the Launch Services database is that more than one application with the same bundle ID can be registered. For example, let’s say I already have the Zwift app installed, and I want to check if its registered with Launch Services. The below command will check the Launch Services database for an application based on the provided bundle ID and return the path to that application.

mdfind "kMDItemCFBundleIdentifier == 'com.zwift.ZwiftLauncher'"

Now if I created my own application, anywhere on the filesystem, within in a few seconds, that app will also be registered with the Launch Services. I placed my app in a Desktop folder as you can see below.

You can also force registration of an app if you don’t want to wait, or are paranoid that it didn’t get auto registered, using the below command.

`/System/Library/Frameworks/CoreServices.framework/Frameworks/LaunchServices.framework/Support/lsregister -f ~/Desktop/MyApp.app`

There are a few reasons why Launch Services allows multiple apps with the same bundle ID, including user vs system installations of the same app, different versions of the same app, and potential backups as well. But how does Launch Services know which app to run when you try open one by specifying the bundle ID? While not officially documented anywhere, I believe its whichever app was most recently registered with the Launch Services database. You can start to see how this might lead to issues right?

Zwift-Specific Behavior

An interesting behavior that I noticed seemed fairly unique to Zwift was during my initial testing of the app’s installation. Before installing the app using the PKG, I had created a test app on my Desktop (MyApp.app) and had modified the Info.plist to have a matching bundle ID to the Zwift app’s (com.zwift.ZwiftLauncher).

When I then installed the Zwift app using the PKG, my test app had been stripped clean of all of its files and replaced with the Zwift app’s. The name of the app was all that remained, but the contents, including the original Info.plist and application binary I had in there was deleted and the Zwift app’s contents put in its place. And the Zwift app started just fine too, thanks to the open command in it’s postinstall script.

So I had just successfully forced the Zwift app to install itself in my chose location (~/Desktop) and have a new application name (MyApp).

I dug into why this was the case and I identified the cause. Within the PKG’s Distribution.xml file is this section:

<must-close>

<app id=“com.zwift.ZwiftLauncher”/>

<app id=“com.zwift.ZwiftApp”/>

</must-close>

CORRECTION: Thanks to a Twitter reply from @theevilbit, I looked more closely at this installation redirect behavior and discovered the actual reason is caused by the following lines included in the PKG’s PackageInfo file:

<relocate>

<bundle id="com.zwift.ZwiftLauncher"/>

</relocate>

This section forces the PKG to search for file location of any apps with the listed bundle ID’s and replaces the first one it finds with the Zwift application. So I could now control the path that Zwift installs itself.

@theevilbit also pointed out that this behavior could be leveraged to exploit PKG’s that implement Launch Daemons, as the Launch Daemon file would likely attempt to execute the intended installation path (e.g. /Applications/XYZ.app) which could be created by a low priv user to achieve local privilege escalation. The Zwift.pkg does not use Launch Daemons so is not applicable here, but will definitely be looking for other PKG’s that do implement Launch Daemons.

Open Sesame

Back to the interesting open command I originally discovered in the PKG’s postinstall script. Linking together this command, with the fact that the Launch Services allows for multiple apps of the same bundle ID to be registered, I thought there must be a way for me to force the postinstall script to open my custom application instead of the legitimate Zwift one it had just installed.

Turns out I was right, and it’s pretty easy.

- Place a dummy .app wherever you want (~/Desktop, etc.) with the matching bundleID. This app will be stripped and overwritten with the legitimate app, so doesn’t matter what this app does as long as it has the matching bundle ID in it’s Info.plist.

- Place the “malicious” .app wherever you want on the filesystem and make sure the malicious .app also has the matching bundleID (

com.zwift.ZwiftLauncher)

-

Unregister the malicious .app from the Launch Services database. This will ensure that when the Zwift PKG is looking for an application to strip and overwrite, it won’t find this application:

`/System/Library/Frameworks/CoreServices.framework/Frameworks/LaunchServices.framework/Support/lsregister -u ~/Desktop/MyZwift.app` -

Register the dummy .app with the Launch Services database. This will ensure that the Zwift PKG does find this application and will strip it and overwrite it:

`/System/Library/Frameworks/CoreServices.framework/Frameworks/LaunchServices.framework/Support/lsregister -f TestApp.app` -

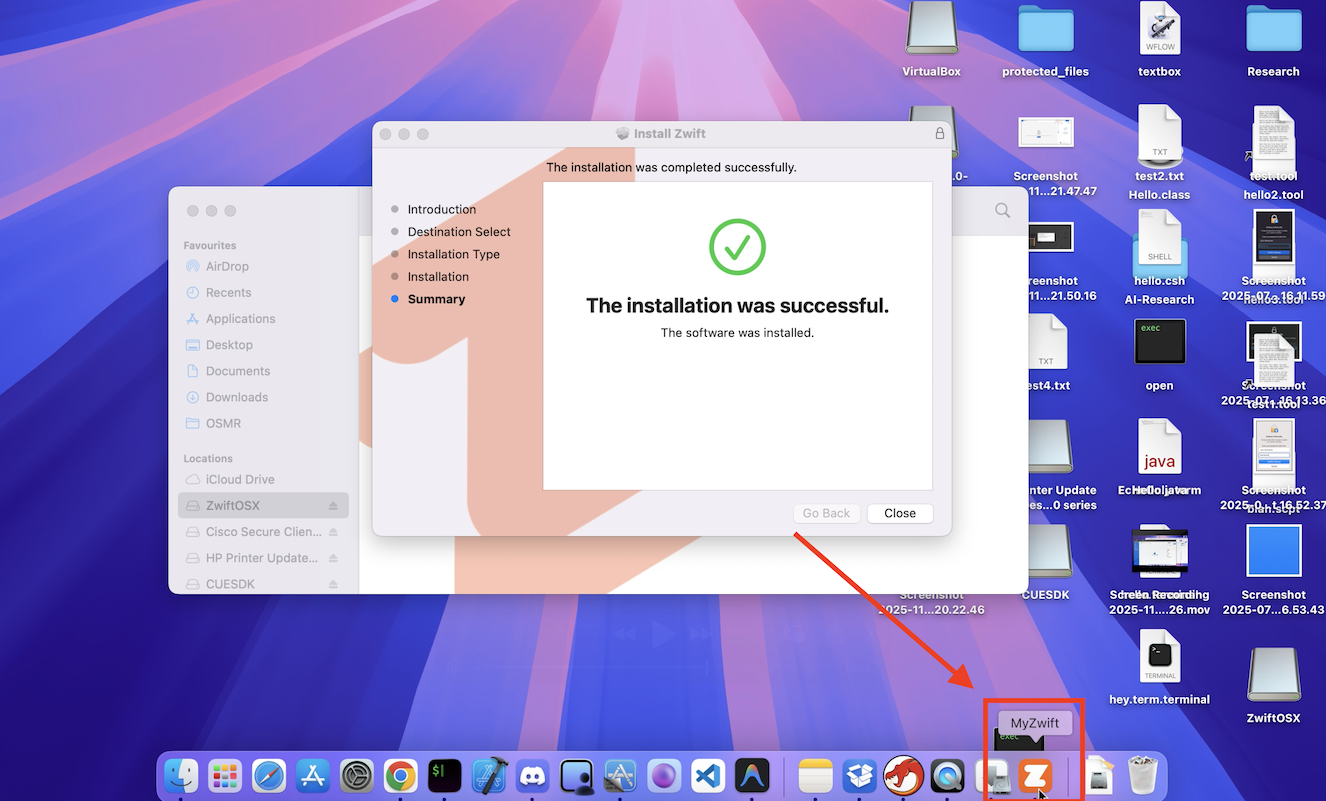

Run the Zwift PKG installer. I think the installer can be run a while after the above 2 steps are taken, but I ran it somewhat quickly after in case it updates the db and registers both of the above apps again.

After running the PKG installer, the dummy app will be overwritten with the legitamate Zwift app. But when the postinstall script runs the open command, it will open our malicious app, MyZwift.

So we successfully got the Zwift PKG to open my malicious app instead of its own!

Is This Useful?

Kind of, but only in fairly niche circumstances. Even though the postinstall script is run as root, the open command runs in the context of the currently logged in user, so our malicious app won’t be executed with root privileges.

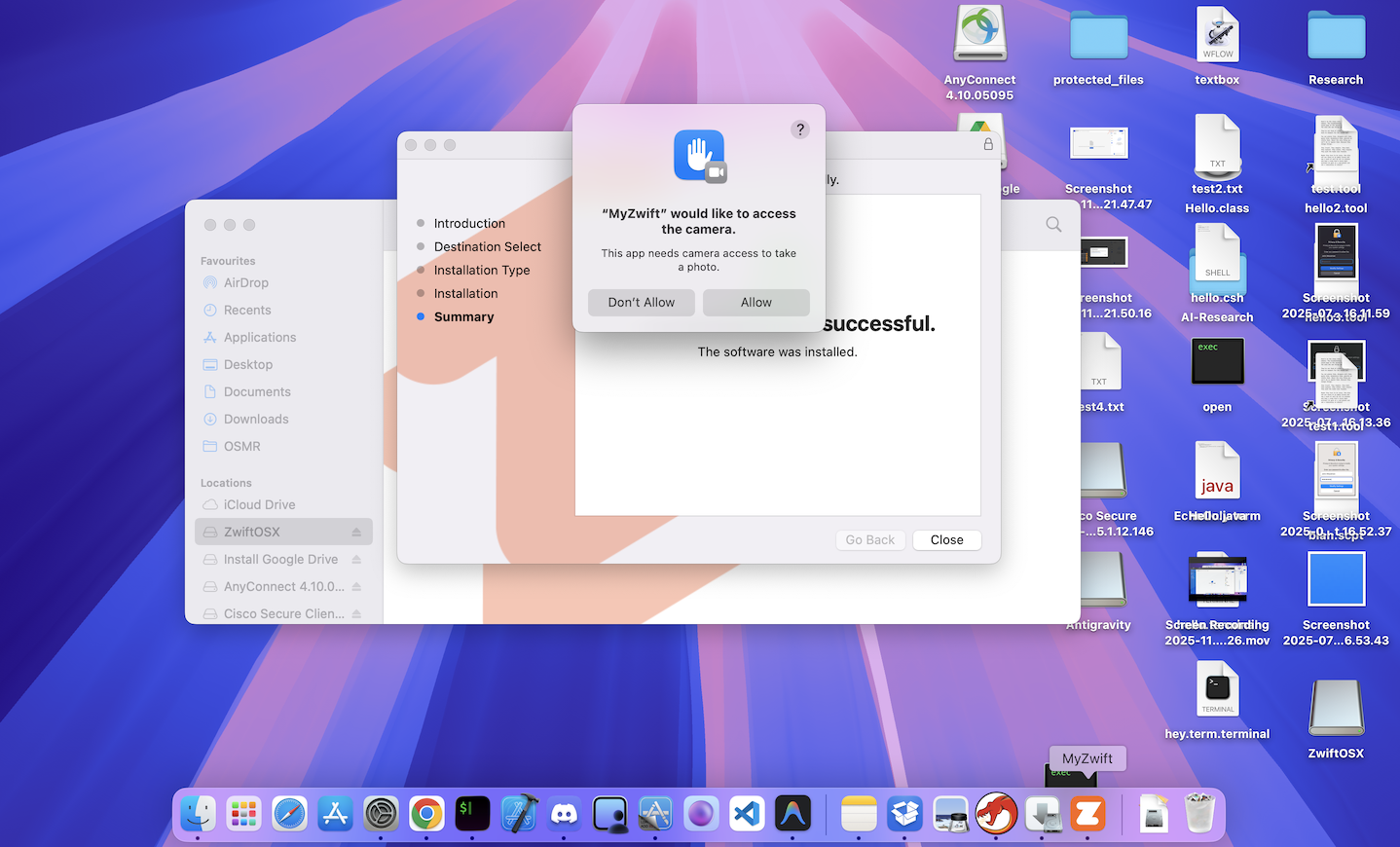

One scenario I could think of is gaining increased credibility when trying to coerce a user to accept TCC permission prompts (camera access, Mic, etc.). If the malicious app has the same Icon and name as the Zwift app, it can prompt for these permissions and appear more legitamate to the user, giving you a much better chance that they will accept. I performed an example PoC where my malicious app is executed after running the PKG installer and prompts the user for camera access, appearing as the legitmate Zwift app (name can be changed to Zwift for even more credibility).

But that’s just my initial thought on how this could be exploited. If anyone has any other interesting ideas or attack scenarios this could be used for, feel free to DM me on X/Twitter.

Conclusion

This was my initial deeper dive into vulnerable PKG’s, and this blog is mostly my way of documentating what I’ve learned, but hopefully it was useful to you as well! I might let the Zwift team know about this weird behavior, even if it doesn’t pose a serious risk. Will update here if I do.